- About

- News

- Events

- Initiatives

- Anti-Racism Collaborative

- Change Agents Shaping Campus Diversity and Equity (CASCaDE)

- Diversity Scholars Network

- Inclusive History Project

- James S. Jackson Distinguished Career Award for Diversity Scholarship

- LSA Collegiate Fellowship Program

- University Diversity & Social Transformation Professorship

- Publications & Resources

- About

- News

- Events

- Initiatives

- Anti-Racism Collaborative

- Change Agents Shaping Campus Diversity and Equity (CASCaDE)

- Diversity Scholars Network

- Inclusive History Project

- James S. Jackson Distinguished Career Award for Diversity Scholarship

- LSA Collegiate Fellowship Program

- University Diversity & Social Transformation Professorship

- Publications & Resources

“University Faculty Are Change Agents”

September 30, 2018

Scholar Story: L. Trenton S. Marsh

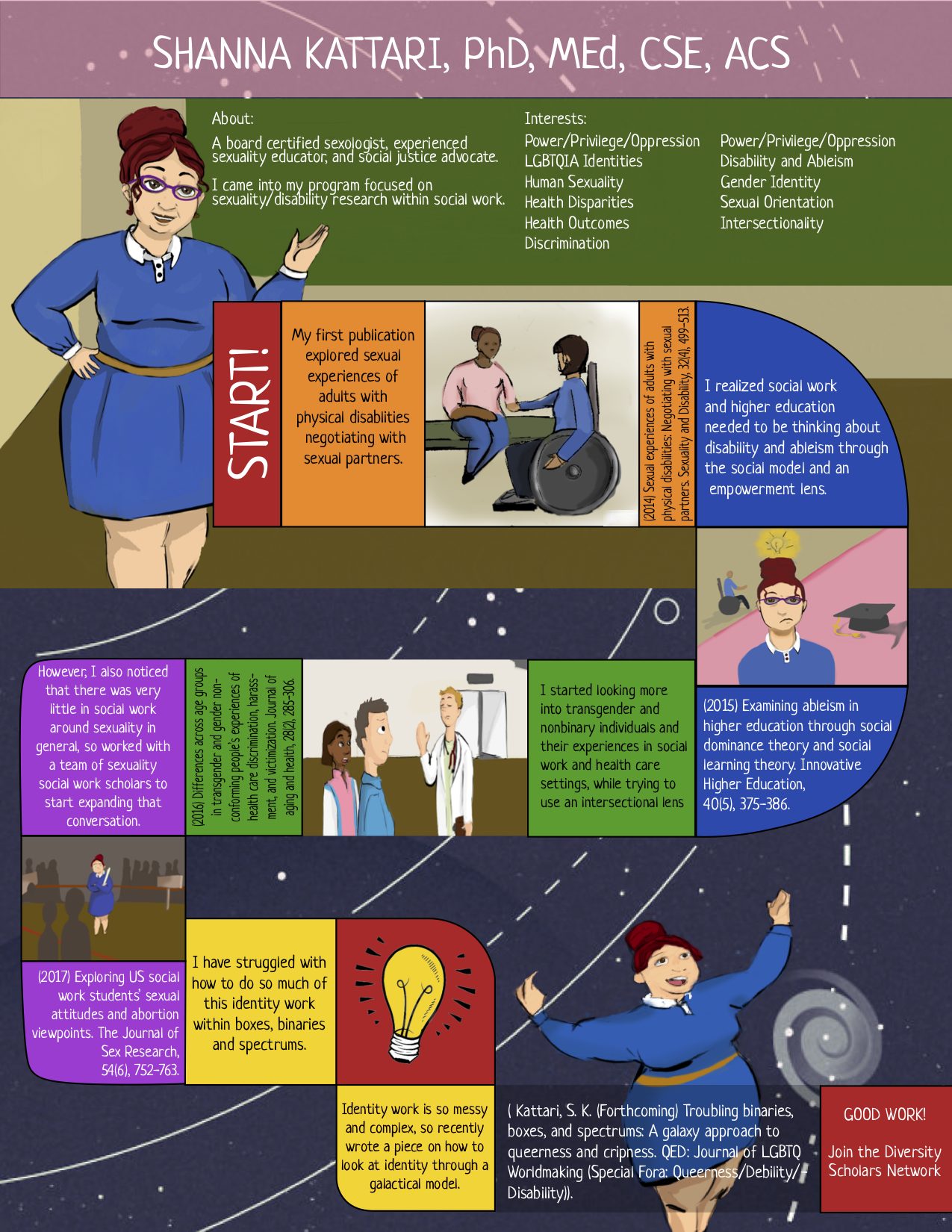

December 7, 2018Scholar Story: Shanna Kattari

"We can't distill people down into one identity, into one box. That doesn't always serve our communities well, and I think about how often people are invisiblized by these boxes or these binaries." —Shanna Kattari

What do you get when combine a board certified sexologist and a certified sexuality educator with a doctoral degree in social work?

The answer: Shanna Kattari.

When you think of social work, most people automatically think of mental health, child welfare, policy advocacy, and community organizing. But for a field that's grounded in social justice, these areas weren't enough for Dr. Kattari. She feels the field is really struggling around disability, queer, and trans issues, and centering those communities’ voices.

I caught up with Dr. Kattari to learn more about her scholarship.

Dr. Kattari is an assistant professor in the School of Social Work at the University of Michigan, with a courtesy appointment in Women's Studies. Her scholarship focuses on three main areas: 1) disability, ableism, and microaggressions around disability; 2) sexuality and gender; and 3) healthcare access, culturally responsive healthcare, and sexual and reproductive healthcare.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

How would you describe your research interests and/or agenda?

This is a question that always trips me up a little bit, because I feel like we are encouraged to have this very clear, step by step, point A to point B to point C to point D research agenda. I feel like my research agenda, much like life and identity work, tends to be a little bit messy.

I see myself as a power, privilege, and oppression scholar. I look at these issues through a health lens, but oftentimes, it means looking at sexuality, and at disability. I look at the health of disabled folks and trans folks, and ask what it looks like for people at that intersection.

I've often gotten bogged down doing scholarship around identity work. This is because the research that's already out there originally came from a very medical, pathologizing model for both the queer and trans community and disabled community. It focuses on what’s wrong and how do we fix them. This is very similar to the historical medical model of disability where disability is seen inherently as negative. How do we fix that?

As research moved to a tolerant model, which is viewing disability as diversity, and queerness and transness as diversity, and how we tolerate these things. Now, I’m trying to move our field towards a social model of disability, which recognizes disability as natural difference and how do we affirm and celebrate our differences in a non-tokenizing way. I’m also trying to move toward this model for gender diversity.

How do we move away from a tolerance framework to really understanding what it looks like to celebrate, uphold, affirm, see these identities not just as options but as equitably valid as other identities? Even though much of my work comes with this health lens, I don't know if I could do any of that work without getting in the mud and really pulling apart some of these identity pieces, and some of these experiences of both overt and implicit discrimination in society around the actual identity work that's happening.

What prompted you to examine this line of research?

I think it was equal parts frustration and maybe feeling responsible from a community standpoint. I'm a certified sexuality educator and sexologist. One of the things I was known best for in my practice was talking about sex and disability. There aren't very many sex educators who do that, especially from a pleasure lens as compared to an STI and pregnancy prevention lens.

I'd go into communities, and we'd talk about a variety of things. They'd be like, "What do we know about this?" And I'd be like, "I don't know." Like, I really don't know. And I'd go and research — and I had friends who are academics, so I'd go sit on college campuses so I'd have access to the journals — and oftentimes the answer was just, "Nobody's touched that."

Much of the work that we've done around sexuality and disability, even from an academic perspective, is around prevention, is around keeping disabled bodies clean and away from other people. There's not a lot of conversation around how do non-disabled folks engage with disabled folks? How do you involve caregivers or care assistants as part of your sexuality if you need them? What does it look like for folks with intellectual and developmental disabilities to consent?

There's not been a lot out there, so I went to graduate school to get my PhD. Then I got into the academy, and realized that at least in social work, we're not actually talking about disability that much period, nonetheless disability and sexuality. And there aren't that many people doing work around queer and trans folks. For a field that's grounded in social justice, I felt like we were really struggling around disability issues, queer issues, and trans issues. So I've been trying to fill those gaps as I start building my own agenda, which is be responsive to the community and also train providers. So whether that's social workers, physicians, nurses, or community mental health professionals, to be better and do better.

What are the key takeaways of your work?

There is no one single issue facing any of these communities. So we can't say it's just employment, or housing, or health. LGBTQIA2S+ communities and disabled communities really are experiencing a lack of awareness, high rates of policies that harm them, high rates of not having access to care, and not having access to support. Whether that's community support, family support, structural support, or financial support. But these communities are really scrappy, and they're resilient.

To queer and trans young people: there is a space for you. Based on the work I do on queer and trans young people and how resilient they are, it reminds me that their voice in general is needed. And we're trying to figure out how to do research that is better at centering your voice and centering your experiences.

We can't distill people down into one identity, into one box. That doesn't always serve our communities well, and I think about how often people are invisiblized by these boxes or these binaries. For other academics, we really need to be more responsive of what communities' needs are and move away from a risk-only model of reporting data. Yes, these are the risks. Yes, these are the disparities. But let’s look at all of the great things these individuals and communities are doing despite all of these hurdles that society is throwing at them.

Are you interested in Dr. Kattari’s work? Feel free to reach out to her. She considers herself the queen of collaboration. She's interested in connecting with scholars working on projects that authentically measure experiences and needs of queer, trans, and disabled communities, especially looking at how that connects to race, immigration status, and aging. Dr. Kattari enjoys using mixed methods, PhotoVoice, digital storytelling, arts based methodologies, and phenomenology from the qualitative perspective. Visit her profile here.